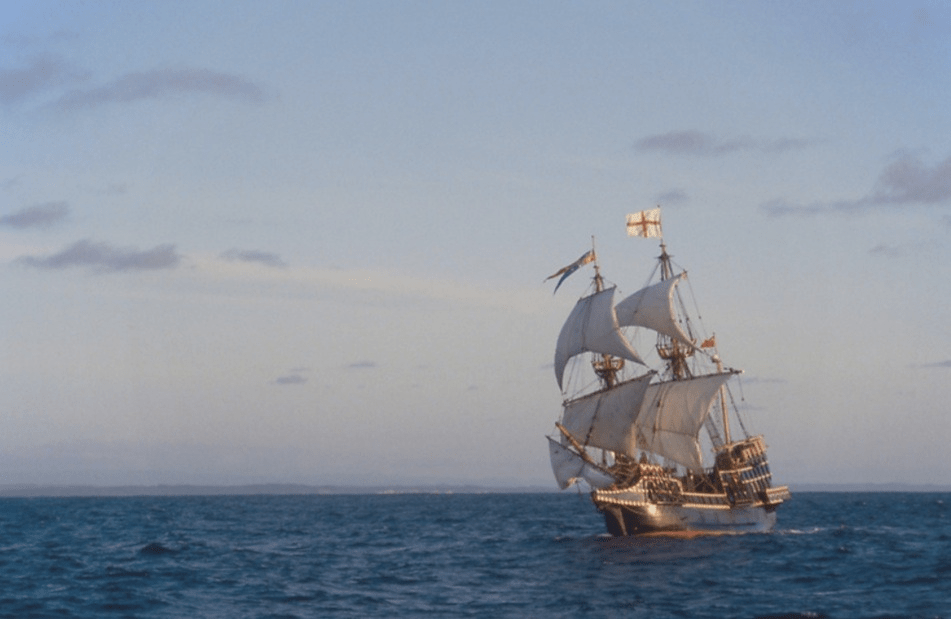

There are not many places in the world where a full-sized galleon replica can survive (and even thrive) as a museum ship. The Golden Hinde replica is that ship and London is that place.

Many ordinary citizens, let alone history enthusiasts, don’t need to be told who Sir Francis Drake was (athough they might not know his ship by name). This Elizabethan “Sea dog” and privateer circumnavigated the world in the Golden Hind in 1577-80, as part of England’s rivalry with Spain. That was before he fought the “Spanish Armada.” I won’t go into the full story here, but nonetheless it’s a riveting read – and has been immortalised in stage and screen several times, among other places. A mountain near my home is even named after this ship.

In addition, the Golden Hinde replica shares several interesting connections with another ship from this blog, the Nonsuch.

I think the Golden Hinde replica is worthy of study because it has made a fairly successful life for itself – first in re-enactments and film and second as a museum ship. Given the substantial costs of keeping up a ship like this, it’s a testament to the story, the organisation, and to London.

For any heritage vessel enthusiast, its a must-visit in London, and somewhat easier to get to than the Cutty Sark.

Specifications

Length: Overall: 121 ft 4 in (37.0 m); Hull: 102 ft (31.1 m); Waterline: 75 ft 1 in (22.89 m) · Breadth: 22 ft (6.7 m) (from Wikipedia).

Benefits of the Build

According to the ship’s website, “Albert Elledge, president of a San Francisco tugboat and harbour-tour line, and Art Blum, a publicist and Vice-President of San Francisco’s Convention and Visitors’ Bureau” formed The Golden Hinde Limited of San Francisco in advance of the 300th year anniversary of Drake’s voyages (which included California).

“In 1968, they commissioned Californian naval architect Loring Christian Norgaard to design the ship. With a seafaring background and a lifelong passion for the history of sailing ships, Norgaard was the ideal candidate to research and prepare designs for the ship. The difficulty he faced was that no detailed record or design existed of Drake’s ship. He spent three years meticulously studying period manuscripts and historical evidence referring to the Golden Hinde and other 16th century ships. The plan for the reconstruction was seen as a milestone in the history of modern naval architecture.” (Golden Hinde website)

Another build where “Experimental Archaeology” was a factor – as techniques from the past had to be researched and rediscovered.

” All components were handcrafted using traditional techniques and materials, from the 22 cannons to the furniture and the Hinde figurehead. Every element was carefully considered for authenticity even down to the small details such as the bottles of scented water Drake is known to have used.” (Golden Hinde website)

The build for this ship occurred in the early 1970s at Appledore, Devon. In fact, these are the same shipbuilders who worked on the slightly more modern replica, the mid-17th Century ketch Nonsuch for the Hudson’s Bay Company. While even a neophyte like me knows that a ketch and a galleon are different beasts, J. Hinks & Son undoubtedly had access to certain heritage techniques learned from the previous build (and others. J. Hinks & Son is probably worth a post of their own in the future). Two riggers working on the Golden Hinde, according to a 1973 article, were in their 70s, but the build also utilised a dozen young apprentices to learn the art. This kind of intergenerational sharing of skills is exactly one of the key benefits of heritage boatbuilding.

“The keel was laid in September 1971, at the Hinks’s shipyard by J. Hinks & Son in Appledore, Devon, and the last rib was lifted on to the keel in March 1972. First, the main timbers that are bolted to the two ends of the keel to receive the ends of the planking, the stem section and the stem-post, were attached. Meanwhile, the sectional plans for the oak half frame, or ribs, were being prepared. This task is usually performed by a loftsman. The name is traditional and derives from mould-loft, the area where the plans of the various sections of the vessel are laid full-size, usually a platform above the main working area. Using the plan supplied, the loftsman starts by laying the outline of the frame full-size on a board, called the scrieve-board. Once the shape is laid, sectional offsets and patterns can then be drawn which are used by the shipwrights to select the right size and shape of timber from the materials in store. These are then sawn and prepared by hand to fit the pattern and returned to the mould-loft for assembling into the frame. Once assembled and bolted, the completed frame is ready to be lifted into place on top of the keel” (Website)

Life after Launch

The ship was launched in 1974 and immediately set sail for California to be part of the 400 year anniversary celebrations of Drake’s visit there. Adrian Small was the Master, and brought with him experience from the Mayflower replica (as Second Mate under the famous Alan Villiers) and the Nonsuch (as Master), among other square-rig sailing ships.

After this commemoration, it sailed to Japan to be part of the filming of Shogun, a book and a movie that captured my teenaged imagination.

The ship spent much of the 1980s visiting ports around the world as an attraction. In 1986, she was one of the premiere attractions for Expo ’86 in my current home of Vancouver. Expo 86 was themed around transportation, so she was joined in that expo by many other heritage watercraft, including a York Boat built at Fort Edmonton Park (A museum close to my heart, and a boat that will form a future post in this blog.)

By JERRYE AND ROY KLOTZ MD – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24741059

Since 1996, The Golden Hinde has been located at a dock in London and used as a museum ship – with only a few brief excursions on the water. It has recently begun to have restoration work done it, but must keep programming all the while in order to pay for the work.

Further Thoughts

The Golden Hinde Ltd is an independent museum, but not a registered charity. They operate for profit, but invest all proceeds back into the ship (or so their website claims). This is an incredibly expensive proposition for such a large ship.

One of the challenges with wooden boats is that they decay in the water, and they decay out of the water. There are few easy solutions for ensuring the vessel is cared for in perpetuity – since this is expensive and takes significant skills. There are choices an organisation can make if they don’t care to keep the ship seaworthy, but that limits opportunities to raise money and their profile (and fulfill their purpose) through sailing and/or appearing in films and tv.

London is not only a gigantic city, but also a tourist mecca – where visitors are hungry for bits of well-known history such as Shakespeare and Drake (the reconstructed Globe Theatre isn’t too far from the reconstructed Golden Hinde or the London Bridge).

A look at TripAdvisor reveals that tourists aren’t happy about having to put up with the ship’s restoration and the requisite scaffolds. I feel for the Golden Hinde folks, who must keep programming in order to afford the necessary repairs. I would hope tourists would appreciate the work it takes to build and maintain vessels of this type, but that would mean this blog wouldn’t be necessary!

The restoration and the celebration of this beautiful ship’s 50th year has prompted the organisation to both celebrate and fundraise.

I think one of the lessons from the Golden Hinde is that life after launch for a full-sized vessel is difficult and requires deep pockets. London and other major tourist attractions are some of the few places where I imagine an independent museum ship not supported by government can sustain itself. Other heritage boatbuilders beware!

Sources

“The Building of the Current Ship” Golden Hinde Website, 4 December 2023, https://www.goldenhinde.co.uk/discover/history-of-the-current-ship

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!

2 thoughts on “Clio’s Armada: The Golden Hinde in London”