I’ve been lucky enough to travel widely in my life. This has often contributed heavily to my passions, including history but more specifically museums and heritage watercraft.

In 2017, my partner and I visited Mossel Bay in South Africa, home of the historic Post Office Tree and I was delighted to find another replica vessel in the local museum: The Bartolomeu Dias Caravel.

The vessel was built for the 1988 commemoration of five hundred years since Bartolemeu Dias, the Portuguese navigator, voyaged around the southern tip of Africa. This early period of Portuguese deep sea navigation is an essential part of Europe’s history and the “age of exploration” (with all its accompanying horrors and modern repercussions).

Dias himself was appointed by King Joao II of Portugal to search for a sea route to India and thus enrich King and Country through the lucrative spice trade. There’s lots more history here, including the amazing story of Prester John, of course.

The Portuguese maritime science and the advances they made in the 16th century while exploring further down Africa’s coast is an incredible story. It is also essential, I think, for understanding the modern world. But this monument was developed in a murky sea of conflicting ideas and perspectives, and its history is not simple.

Dias didn’t make it to India, that would be for his successors to accomplish. What Dias did do was make landfall in what is now South Africa, possibly the first white man to do so. He also shot an Indigenous Khoi person with his crossbow during an altercation at a fresh water source.

I’ve talked before, namely with the HMB Endeavour about how fraught commemoration can be. Replica vessels are often monuments, and thus subject to the same critiques. Can a reconstructed vessel engage visitors with this history without implicit and uncritical celebration? Let’s see how the museum in Mossel Bay handles it.

Specifications

23.5m in length and displaces 130 tonnes, according to Mossel Bay tourism.

Benefits of the Build

According to the Mossel Bay Dias Museum’s website, the Portuguese Sail & Training Association (APORVELA) took on the task in the 1980s to build a “caravel-type” for the commemoration of Dias’ voyage. Caravels are two or three-mast, shallow-draught ships iconic to this period of Iberian seamanship. However, their construction is not well understood, even today, so the reconstruction was full of guesswork and experimental archaeology.

Thus this ship is not technically a replica of one specific vessel, but rather representative of the caravels used in Dias’ voyage. This explains why it is named after the explorer himself, rather than one of his vessels – the names of which were not known anyway (this build and its re-enacted voyage were plagued by a lack of historical records).

“The historical appearance of the caravel was maintained in the design of the topsides, deck arrangement, steering gear, masting, rigging and sails. However, below deck, the design was adapted to allow for modern sleeping arrangements and motorised engine.” (Dias Museum website) Perhaps if the Nonsuch replica had done the same two decades earlier, a voyage across the Atlantic might be more conceivable!

The shipyard of Samuel & Filho’s in Vila do Condo, near Oporto in Portugal was the site of the build. “The hull was made of pine and oak and equals the width of a modern tug. It had a displacement of about 130 tons, which included 37 tons of ballast, made of concrete and granite blocks from Lisbon. The ship has two masts and two lateen sails.” (Dias Museum Website)

According to a report by one of the leaders of the project, the caravel was a sturdy build, but owing to its imperfection as a replica “her sailing qualities were somewhat disappointing.” (quoted from a report in Witz, 2006).

The Bartolomeu Dias Museum Complex website is curiously quiet on who funded the build (for reasons that will become apparent below), but it is clear this was a project bankrolled in large part by the government of South Africa. By the 1980s, Dias was becoming a desired symbol for that country and an opportunity to collaborate with Portugal outside of the anti-apartheid boycott.

Samuel & Filho’s built another caravel, Boa Esperança, launched in 1990 that is still afloat in Portugal and used as a museum ship. Their skills as historical shipwrights, developed under contract to South Africa’s government, undoubtedly continued to serve.

Life after Launch

This replica caravel, named Bartolomeu Dias after the navigator, was launched off Portugal in late 1987. Captain Emilio Carlos de Sousa sailed it for three months to Mossel Bay in South Africa, arriving 3 February 1988.

There was tension between the voyage as re-enactment and the Dias ’88 festival waiting for it at Mossel Bay with all of its South African and Portuguese dignitaries. The Captain and the crew, while willing to take advantage of their onboard engine, wished to round the Cape of Good Hope on their own. The festival organisers were concerned not only for their timeliness, at one point suggesting a tow, but also that the vessel dispose of its “gasoil” containers from the deck before it arrived, for appearances. (Witz, 2006). I can understand the latter, but the former would irk any Captain.

De Sousa’s crew was both Portuguese and South African, and while the 500 year date was significant, this arrival would have been during the latter country’s period of apartheid, a system of institutionalized racism that segregated and robbed racialised groups of power. In fact, the Dias ’88 festival and the caravel’s arrival was during the height of the anti-apartheid movement, and only two years before Nelson Mandela was released and the negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa began.

Upon the caravel’s arrival (on time) at Dias ’88, “[South African president] PW Botha went aboard the SAS Protea of the South African Navy and welcomed the vessel while it was still at sea. Surrounded by a navy flotilla, the caravel then made its way into Munro Bay in a scene that South African Panorama, an official publication of the National Party’s Bureau for Information, described as ‘moving and unforgettable’,” (Witz, 2006)

After arriving in Mossel Bay and the festivities of Dias ’88, Bartolomeu Dias was hauled onto land and inside the museum for permanent display, where it still lays.

The Dias Festival is still celebrated annually at Mossel Bay, although “Dias” now arrives via motorcycle and raps a song about the community. (Seriously).

Further Thoughts

Leslie Witz, a historian from South Africa has a fascinating paper on the Dias ’88 festival. In 1988, the South African government was in the process of trying to “re-brand” apartheid, having written a new constitution with roles and powers for coloured (mixed race people) and Indian South Africans, and trying to characterise majority black opposition (who still had no political representation) as lawless and communist, not “race-based.” This was a new apartheid.

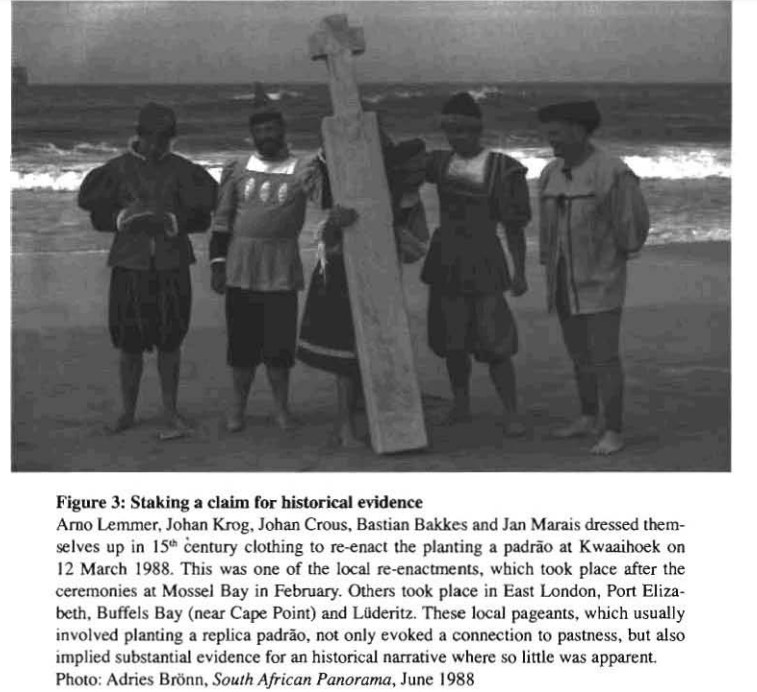

Thus assertions that “the Dias commemoration as ‘a festival for whites’ were repeatedly denied”, despite the festival being conceptualised as a commemoration of the first white man (Dias) entering South Africa. (Witz, 2006) Caio Simões de Araújo points out that Dias hadn’t been celebrated overmuch in early Apartheid, with more commemoration given to the Dutch “pioneers”, but under the new brand, Dias was more acceptable as a figure of commemoration. (de Araújo, 2022)

Witz describes the Dias voyage as being intentionally and sometimes forcefully framed around Portuguese exploration and navigation in world history, rather than about colonisation of South Africa. The government and organisers went to great lengths to make the festival appear multicultural and to present Dias as a symbol of diversity, or at least neutrality. (Witz, 2006)

Portugal was at the same time engaged in a momentous transformation itself, having lost its colonies in the 1970s, emerged from dictatorship, and trying to grow economically. Celebrating Portuguese exploration was a suitable nationalist goal. Collaboration with the increasingly isolated South Africa was ultimately deemed acceptable.

Reading Leslie Witz’ account is amazing, as the festival is full of contradictions and painfully gymnastic attempts to fit complex history into a modern commemorative event with pro-apartheid aims. The peak of the ridiculousness comes when a re-enactment of De Sousa’s landing is undertaken with white actors wearing black masks to portray the Indigenous inhabitants. Coloured South Africans were boycotting the festival, and the majority black population were not interested. “In a most astonishing reversal ‘whites’ had to masquerade as ‘blacks’ in order to perform late apartheid’s festival.” (Witz, 2006)

These are only some of the stories from Leslie Witz’ account, and none of them are presented at the Dias Museum in Mossel Bay. There are photos of the construction, voyage, and festival, but they miss any of the conflict or tension in a story like this. Neither do they grapple with the larger international issues surrounding settler colonialism.

Caio Simões de Araújo has also studied Dias and his commemoration at Mossel Bay. “Dias can be productively seen not only as a historical symbol of pre-apartheid early modern European maritime exploration (which he also was), but, more importantly, as the expression of a twentieth century settler colonial mythology.” He further argues that Dias’ commemoration – in these contexts – supports apartheid and colonialism. (de Araújo, 2022)

This is the danger of heritage shipbuilding as commemoration and community building. And as enthusiasts, it is important for us to remember that commemorations are the tale of two eras: not just the event or figure or boat being commemorated, but the time in which people decide to fund, build, and sail these ships. Why did they do so and what narrative were they choosing? What community is being served by the reconstruction and what communities might be excluded?

The Bartolomeu Dias caravel is a feat of shipbuilding that rediscovered and shared priceless heritage skills. It commemorates an amazing period in Portuguese and world history, but that’s not all it represents. Obscuring the rest of the story, even sometimes unintentionally, as the museum does, is irresponsible.

Maybe South Africa has it worse because of the public sins of apartheid. Maybe Canada, the U.S., Australia and other settler countries get off too easy when they celebrate their ships or their “first white person to do something” moments in history. Regardless, this museum got it wrong.

This is a complex issue and I don’t want to belabour the point in a blog. I welcome messages and cordial discussion on the matter.

Sources

Leslie Witz, “Eventless History at the End of Apartheid: The Making of the 1988 Dias Festival”, Kronos, no 32. (November 2006)

Caio Simões de Araújo (2023) “Must Dias fall? The politics and history of settler heritage in Southern Africa”, Settler Colonial Studies, DOI: 10.1080/2201473X.2023.2278996

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!