In the 1990s, the Britannia Shipyard National Historic Site Society built two replicas of the Fraser River flat-bottomed skiff. These craft fished the Fraser River in what is now British Columbia in the 1870s and 1880s before being replaced by round-bottomed boats. They could be maneuvered by oars as well as sprit-sails in favourable weather.

As some of the earliest European-style small watercraft in the area, the flat-bottomed skiff deserve recognition. And their story is a fascinating one for me, particularly – and one I learned while working a contract at Britannia Shipyard, a wonderful historic site full of fascinating stories. .

BC has a wealth of heritage boats, and some of them – like the flat-bottomed Fraser River skiff – have the potential to navigate our faulty memories and lead us to a better understanding of ourselves and our history.

Specifications

Length: 20 feet

Beam: 5 feet 6 inches

Oar: 5x (9.0′), 5x oar locks

Sail: Yes – mast (15 1/2′), sprit pole (13.0′), sail (canvas), 4x lines, 2x belaying pins (wooden), mast collar (metal)

(Source)

Benefits of the Build

I don’t have a lot of information on the building of these skiffs, and they are nearing thirty years of life. I hope to interview the Britannia Shipyards National Historic Site Society about the process, but that’s also hoping that someone from the original build is still active with the group.

Maritime heritage consultant Charles D Moore describes these skiffs as “fairly straightforward craft to build” with a “construction method well suited to the broad planks of red cedar supplied by the first milling operations underway in the Lower Mainland.” (Moore, 2007). He suggests that its construction details and proportions might properly place it in the “bateau” family of flat-bottomed boats in North America that share a Laurentian heritage.

Nonetheless, Moore isn’t sanguine about the accuracy of the Britannia Society’s product. They are based on a plan drawn up in 1990 based on some historical evidence but, he feels, not particularly accurate to the photographic record. (Moore, 2007) This is a really interesting case of sparse historical sources leading to speculation and experimentation.

No Fraser River skiffs survive into this period, but Moore suggests that photographs can provide some details. “It is a flat-bottomed boat, with a hard chine, no keel, and is sharp fore and aft. The topsides are laid clinker with no more than three strakes per side. Frames are not numerous, placed perhaps every 24-30 inches, with the futtocks overlapping the floors like knees. Chine logs are not evident. Many boats had no decks, but later boats in particular had short decks on across the bow and, more rarely, narrowed side decks. Two rowing stations were standard, the “puller” sitting on the central thwart while the fisherman typically rowed facing forward and standing at the aft pair of oarlocks. A centre-board case was braced by a thwart at each end, while a third thwart forward partnered a mast.”(Moore, 2007)

Moore relates that in 1990, naval architect David Moore (no relation) made plans for the Fraser River skiff based on a description by a boatbuilder named Carter in 1911. However, these plans don’t accord with his analysis, above, of photographic evidence for the early skiffs.

“It is not my wish to knock the effort that went into the Britannia Heritage Shipyard [Society] interpretation of the Fraser River skiff…not one, but three boats were built on the Carter/Moore model, and the effort to produce the plans, raise funds for the materials, and organize the final building of these boats was tremendous. For five or six years through the mid-1990s the boats were successfully used on the water at regular events.” (Moore, 2007).

Life After Launch

The skiffs are now housed at the Britannia Shipyards National Historic Site in Richmond, BC. This is a wonderful site where I worked for almost two years. It hosts an annual maritime festival, as well as many other programmes. The skiffs are stored on land, and have occasionally been used on the water.

I was lucky enough to get to work on writing and installing signage for them, as I think their significance is often missed. Nonetheless, these skiffs are only two of the many amazing ships – new and old – displayed at Britannia. And I must admit, their history is tailor made to appeal to me – and not everyone.

Further Thoughts

Charles Moore wrote several articles for Wood and Water examining some of the early planked boats of B.C.’s history. They are excellent sources, appealingly written, and outline some of the challenges in understanding Pacific Canada’s maritime history – namely a lack of surviving examples.

In terms of the Fraser River skiff he describes it as being used “alongside Native dugouts from the outset of BC’s salmon canning industry in the 1860s. It continued in use on the Fraser until the fishing grounds expanded into the Gulf of Georgia in the early 1890s, when the larger, more capacious and more seaworthy roundbottomed sailing gillnetter began to supplant the skiff.” (Moore, 2007)

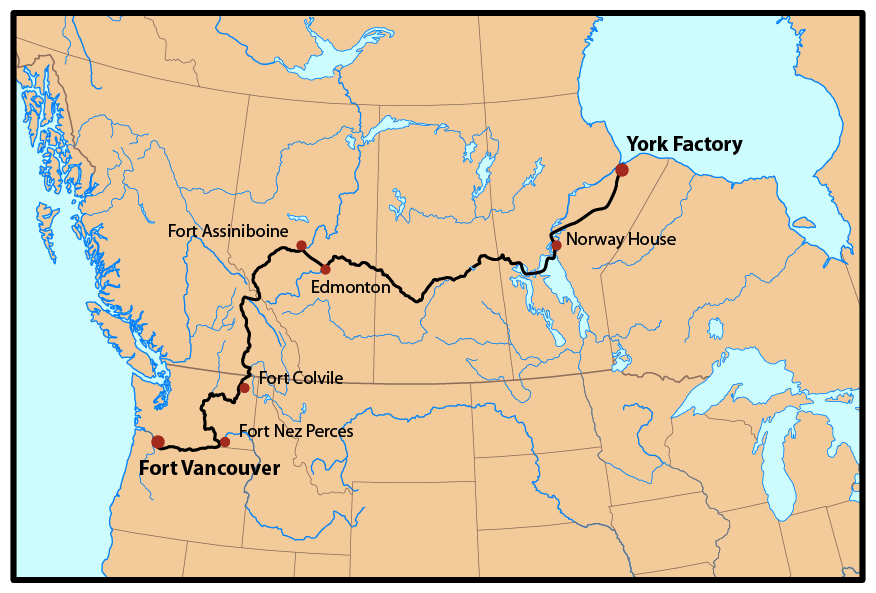

Reading Charles Moore’s articles were frustrating as well as fulfilling. He wrestled with the origins of flat bottomed skiff, origins that I thought were obvious. “How a bateau type emerged on the Fraser River in the 1860s is a bit of a mystery.” Really, Charles? Ever hear of the fur trade?!

(Note that Fort Vancouver is Vancouver, Washington – not Vancouver, B.C.)

I suppose its because British Columbians in specific and Canadians in general don’t often think about the fur trade period in history (which is what I studied in University and what much of my museums career has focused on). In my experience, British Columbia tends to think of its history as consisting of two primary parts: thousands of years of First Nations stretching back to time immemorial; and a colonial history starting in 1859 with the making of BC as a British Crown Colony.

But if you got into one of Britannia Shipyards’ flat-bottomed river skiffs, push off, and start to oar into the Fraser River, you’d have the chance to peer into a liminal period. During the late 1700s and early to mid 1800s, the Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Kwantlen First Nations were a few of the hundreds of distinct, vibrant, and sovereign entities of the coast, and co-existed with a significant European mercantile enterprise. As early as 1793 Europeans and Indigenous Métis navigated the rivers, sailed the coasts, and built trading posts (and their accompanying settled communities) – sometimes as allies, sometimes as interlopers, often as tolerated guests.

The most well-known of the great fur-trading companies of the pre-colonial period is the Hudson’s Bay Company. But the North-West Company, Russian-American Company, and John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company joined them at various times. The HBC and Nor-westers had trading posts stretched across what is now known as Canada – from coast to coast to coast. A trader (and his traditions) could embark from the St. Lawrence and be at the Arctic or Pacific within a year by canoe, York boat, packhorse, and bateaux.

As with the famous Red River Cart, the Métis craftsmen who worked in these Forts often mixed European (including New France) building styles with First Nations techniques and their own innovations. In this sense the bateaux, York Boats, and flat-bottomed skiffs used in the fur trade can be considered partly Indigenous crafts themselves, as well as European (Also see my post on the Fort Langley bateau).

Why should we care? There are things to be inspired by, ashamed of, and to puzzle at in the fur trade period. For me, the Flat-Bottom Fraser Skiffs themselves link the West Coast to the prairies, Arctic Canada, the Canadian Shield, and the St. Lawrence River Basin. This wood-planked boat and its boat-building tradition is iconically Canadian. And these skiffs, while not necessarily Indigenous themselves, also link us to Métis boat-builders and their Indigenous nation that formed post-contact (itself a fascinating concept) and made the prairies and rivers their highways and homes.

In the end, Charles Moore and I agree quite wholeheartedly. Canada has not adequately preserved or recorded its maritime history, especially on the West Coast, and neither has it fully acknowledged its history in a more broad sense.

Sources

Moore, Charles D. “Reconstructing Traditional Small Craft of British Columbia Pt 1″ Wood and Water, Spring-Summer 2006

Moore, Charles D. “Reconstructing Traditional Small Craft of British Columbia Pt II: The Fraser River Skiff” Wood and Water, Spring-Summer 2007

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!