In 1968 the Nonsuch replica ketch was built, commemorating the 300th anniversary of its voyage and in advance of the tercentenary in 1970 of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s charter.

Few corporations have had such a tremendous impact, for good and for ill, on modern Canada (and areas of the U.S.) as the Hudson’s Bay Company. Before missionaries, before loggers, and before settlers entered most parts of this country, the HBC or its contemporaries were there bartering, swindling, and begging for fur or access to fur. To bring in the trade goods First Nations and later Métis trappers demanded, the HBC sailed tallships in and out of the bay.

The Nonsuch, a ketch that had previously served in the Royal Navy, was purchased by a consortium of merchants and sailed into the Hudson Bay in 1668 (along with the Eagle). It spent the winter trading for beaver skins with the Cree and returned to England in October 1669. In 1670 the HBC was granted its charter to trade into all waters draining into Hudson’s Bay. The original Nonsuch‘s history is not known after this.

The replica was undertaken by the HBC in advance of the 300th anniversary of the Charter, purely as commemoration. As 1967 was also the centennial of Canada’s Confederation, there was likely a great enthusiasm for nationalist commemoration, not to mention abundant funding. The HBC was also happy to undertake what amounted to a tremendous PR exercise.

Specifications

Length overall: 16m (54 ft)

Draught: 1.8m (6ft)

Beam: 4.6m (15ft)

Benefits of the Build

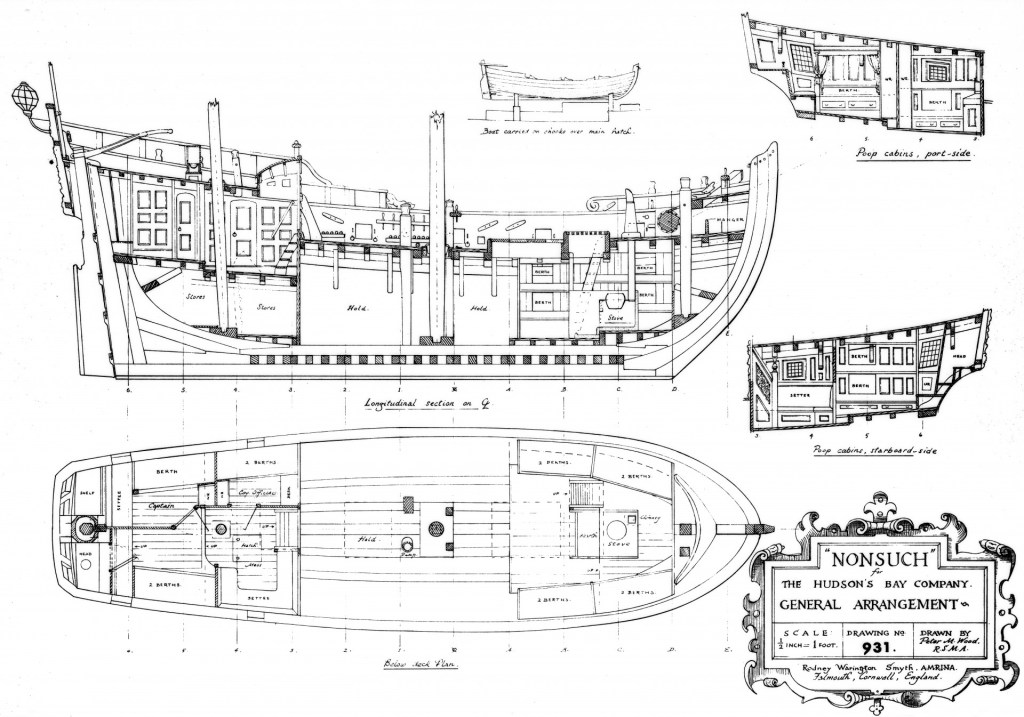

According to the Manitoba Museum the research and plans for the replica were undertaken in the 1960s by Rodney Warrington Smyth of Falmouth, Cornwall in England. It was built at J. Hinks and Son Shipyard at Appledore, Devon.

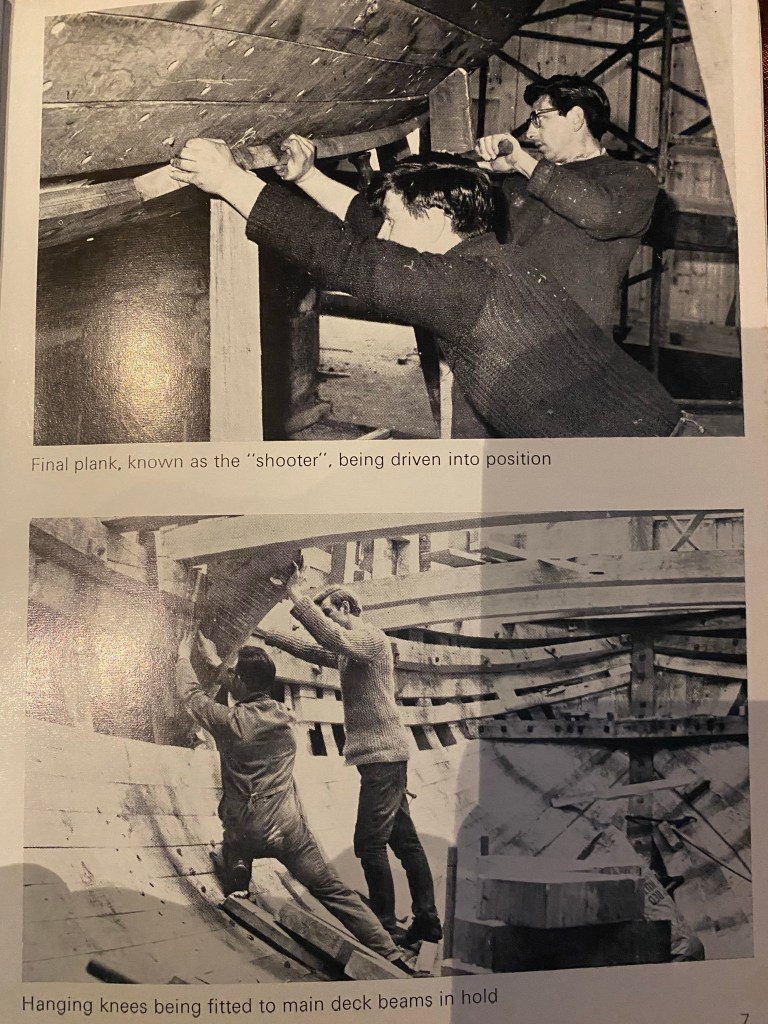

A pamphlet published by the HBC in 1969 provides more details as to the build. Extensive research was “drawn from the Archives of Hudson’s Bay Company, 17th century models, paintings and near contemporary accounts of shipbuilding techniques in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich…the result is as near a 17th century ketch as is practicable to achieve.” So there was a measure of experimental archaeology, in terms of figuring out how it was done.

“The vessel was constructed of the same types of wood and with the same methods and techniques as would have been used in the seventeenth century. The sails are made of Navy flax canvas woven in Scotland and, with the exception of the Spritsail, were hand sewn.” (From the Manitoba Museum panel).

This experiment in PR was nonetheless a benefit to traditional shipbuilders and traditional techniques. Wooden shipbuilding, even in the 1960s, is not necessarily a profitable industry – especially when using oakum caulking and handsewn sails. A private company’s vanity can help fund and pass on traditional techniques where a more standard shipbuilding industry can not.

The 1969 pamphlet records somewhat triumphantly that “skilled men who had learned their trade as boys repairing Britain’s last wooden sailing ships” helped Alan Hinks cut and erect the frames, bolt them together, and steam-bend planks for the hull. The pamphlet confirms “no laminated timber was used, [such as the Endeavour replica used] only seasoned solid wood collected form the timber yards all over southern Britain.” It is somewhat surprising that timber of the age and size required was still available. Many shipwrights and enthusiasts I have spoken to in the last few years confirm that accurate historical shipbuilding is almost impossible now due to the lack of old-growth lumber.

Life after Launch

The Manitoba Museum records that the vessel launched in late 1968 and sailed the English Channel the next summer. It was then shipped across the Atlantic on the deck of another ship without its rigging. It was refitted at Sorel, Quebec, and then sailed to visit ports in Canada and the USA.

The 1969 pamphlet contains clues as to why the Nonsuch replica was not sailed across the Atlantic and why it later travelled to the West coast via land. Alan Villiers wrote about the problems involved in sailing the replica, though the Master was his old colleague Adrian Small (Villiers and Small had sailed together on the Mayflower II replica). Villiers describes the accurate rigging of the ketch as being quite difficult and particular, (“a challenging little ship”) even compared to the Mayflower. I suspect a full ocean-crossing sail was considered too dangerous and impractical, even for a pro like Small.

(Add to that that the Nonsuch is actually quite tiny and the lower decks were not built for modern comfort – it would have been something of a tall order to find a crew willing to sail across the Atlantic in her!)

After Nonsuch‘s visits to in the East, the move across land to the west coast was a huge project in itself. Riverton Boatworks Ltd hauled the ship from Lake Superior to the Pacific with a stop at Winnipeg in 1971. Transported on a custom cradle, it travelled overland through the Prairies to Seattle, Washington and then sailed up to Vancouver

Since 1973, it has since been displayed to the public at the Manitoba Museum, which was always the long-term intention of the HBC.

Further Thoughts

The heady Canadian nationalism of the 1960s and 70s may have welcomed the arrival of the Nonsuch, and the displays at the Manitoba Museum undoubtedly helps visitors understand the history of the HBC. Nonetheless there is no question that this replica was built purely as a celebration of a history that not all Canadians would find worthy.

The fur trade and the HBC are complex historical topics, and I don’t pretend expertise, but I don’t mind opining that while they were at least not wholly objectionable trading partners for hundreds of years, they nonetheless were a colonial enterprise. They also “celebrated” the bicentennial of their charter in 1869-70 by selling Rupert’s Land and the Northwestern Territory to Canada – land that they didn’t own and had not treated for (as the Royal Proclamation requires). Indigenous people were not consulted. This eventually led to the Red River Resistance and the Numbered Treaties, but nonetheless the Nonsuch and the HBC’s legacy is not worthy of uninterrogated celebration.

Museum ships like this one are best used in heritage facilities to provide an immersive and three dimensional setting for telling stories of the past. But their stunning presence and size, much like Trading Post reconstructions can tell an implicit story of grandeur when compared to the “more humble” tipi and the birchbark canoe – which of course have their own beauty in design and utility. Museums must be careful throughout the implicit, visual message is balanced with solid interpretation and context.

Sources

Greenhill, Basil and Villiers, Alan Nonsuch: Hudson’s Bay Company Printed in England by Alabaster Passmore & Sons Ltd, London and Maidstone. 1969.

“HBC Heritage: Nonsuch“. Hudson’s Bay Company. 1979. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!

I remember touring the Nonsuch in Toronto Harbour, as a kid. Even then I remarked on how meagre it was in size and asked my dad if it was a small-scale model. He – a Master Mariner – assured me that it was full-size. Now I – a marine professional myself – remain awestruck that a mere 16m vessel could have sailed the North Atlantic and northern waters, let alone that so many men could have lived aboard.

LikeLike

Thanks for that story. I attribute the decision not to sail it across the Atlantic to the difficult job the crew had sailing it, but I should have acknowledged the cramped quarters!

LikeLike