I was lucky enough to visit Sydney last year (2023) and even more lucky to experience the Australian National Maritime Museum (stupendous) and its exhibit of the replica (or simulacrum, if you prefer) of His Majesty’s Barque, Endeavour, the famous ship of Captain Cook.

It was a stunning exhibition and the volunteer tour guide was knowledgeable and very happy to share his knowledge with me. I also purchased a museum publication on the replica from which the information on this blog post comes.

Tall ships are among the most frequent replicas constructed. I think this exemplifies the commemorative impulse in heritage shipbuilding, and the majesty of the age of sail. Unfortunately while they might be easier to find fundraising for the build, they’re also the most difficult to find a life for after launch, owing to the expense of maintaining and sailing them.

But there are other difficulties with this story.

The Specifications

Overall length: 33.3.m

Length of lower deck: 29.77m

Breadth: 8.89m

Depth in hold: 3.45m

Carring capacity (burthen): 397 gross registered tonnes

Displaced volume: 550 tonnes

Sail area: 926 sq. m

Mast: main 39m, Fore 33.5m, Mizzen 24m

(Source: HMB Endeavour Published by the Australian National Maritime Museum, 2006.)

Benefits of The Build

The reconstruction of HMB Endeavour could and does fill a book. I’ll try to summarize. One of the things I appreciated was that it was not a 100% accurate reconstruction. Unlike an Experimental Archaeology approach (such as Napoleon’s Trireme), or an overemphasis on accuracy, the approach of the Fremantle, Australia project team was practical and commemorative. They wanted a ship that could be built and sail for many years. The original Endeavour only lasted 29 years and was built in the U.K. using contemporary materials and techniques. The replica was different.

The project team compromised: the ship would be exhaustively researched for historical accuracy. Materials would be chosen for the greatest longevity, but would not be allowed to compromise the original method of construction, nor the spirit of the ship. Modern tools would be used when required.” (HMB Endeavour, 2006)

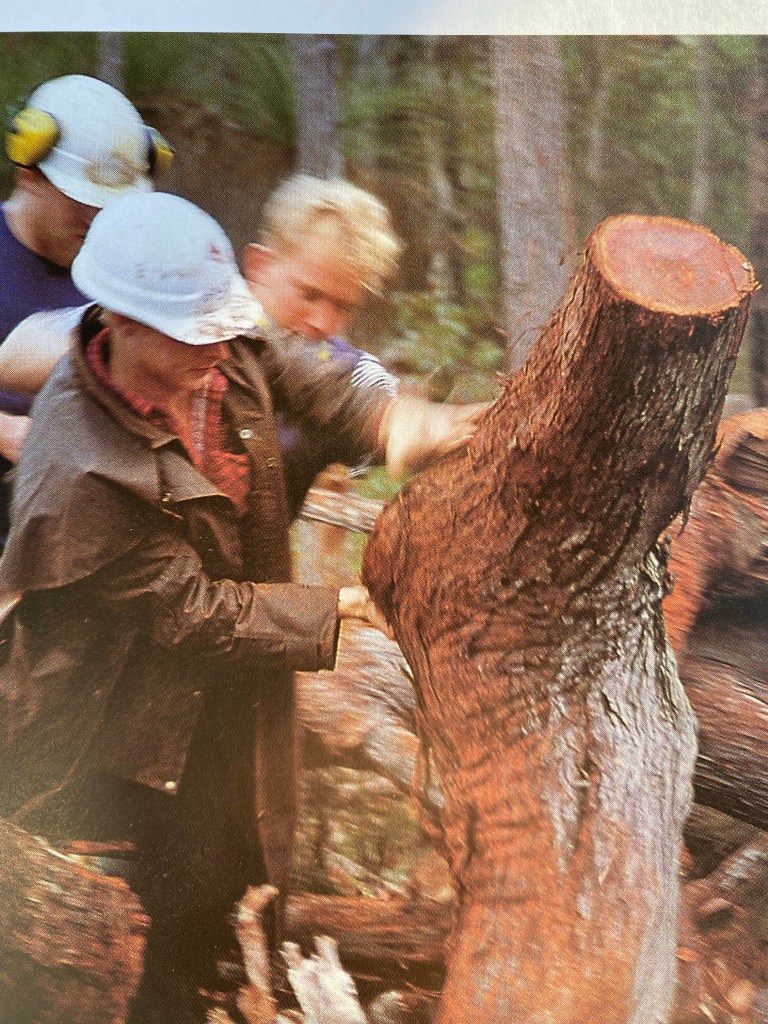

This meant that instead of oak, the West Australian hardwood jarrah was used. Oregon fir replaced Baltic pine, and a variety of synthetic and natural fibres were used for the rigging.

Most craftsmen dealing with wood know that the large amounts of old growth timber (of superior quality) are no longer available (nor should they be). The Fremantle team used laminated wood where large sized timber was not practical or available.

“All planking was fastened in the traditional manner using thousands of trunnels (wooden nails). However below the waterline and at the ends of the planks coach bolts were used instead of iron spikes for added security. As each piece of timber was shaped it was treated first with an epoxy based preservative and finally red lead.” (HMB Endeavour, 2006)

The build took six years at a cost of over AU$17 million. A triumphant number of craftsmen and women were involved in the reconstruction, learning, sharing, and preserving a huge variety of heritage skills.

Life After Launch

“Endeavour has visited all southern and eastern states of Australia, the north and south islands of New Zealand, Ascension Island, Rodriguez Island, South Africa, Madeira, Britain, Channel Islands, Teneriffe, St. Helena Island, St Malo, the east and west coast of North America, the Panama Canal, the Galapagos Islands, Hawaii and Fiji, and completed her first circumnavigation of the world in the year 2000.” ((HMB Endeavour, 2006))

While the vessel was built and launched by the non-profit HM Bark Endeavour Foundation, in 2005 she was acquired by the Australian Government (likely due to costs). She is now housed and displayed in the Australian Maritime Museum in Sydney, Australia, but still sails from time to time. It has an international crew, but when I spoke to the volunteers they said they were attempting to train a local Australian crew to cut down on costs, which are frankly astronomical.

Further Thoughts

It is worth noting here that while HMB Endeavour is an incredible work of craftsmanship and heritage, it is nonetheless a fraught heritage. Captain Cook was an undeniable colonist and his voyages furthered colonial projects which dispossessed Indigenous people of their land and freedoms – in Australia and elsewhere. His death in Hawaii in 1779 is worthy of study, but not necessarily of condemnation.

Similarly this reconstruction has a hard time (though not impossible) grappling with the complexity of this historical legacy. In 2019 some Maori groups in New Zealand/Aotearoa refused to participate in a re-enactment involving the Endeavour, even when the organizers thought they had made the event bicultural. Read more here.

Reconstructions cannot be separated from their colonial past, nor should they be. Complexity is baked into history and cannot be ignored – even by enthusiasts. Any discussion of the Endeavour and of Captain Cook’s voyages, have to go along with adequate acknowledgement of their impact and their place in history. Reconstructed ships, much like pioneer villages and historic sites, are generally seen (and sold) as commemoration, not as dispassionate historical study. And their grandiosity means that their implicit visual message can overshadow (Sometimes literally) any deeper interpretation.

It doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy them, but we can’t enjoy them without recognising and acknowledging the salient aspects of their history and its impact today.

HMB Endeavour Published by the Australian National Maritime Museum, 2006.

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!

One thought on “Clio’s Armada: The Endeavour and the Australian National Maritime Museum”