Tom Long, 2025

Mixedness is not always about blood quantum. The perception of how prominently the person is living in their culture can lead to impressions of being diminished or diluted. But that perception also pressures Indigenous people to live a “plastic shaman” or “feathers and buckskin” version of their culture. There are also factors, including policing and legitimacy in academic or professional circles, that might pressure Indigenous people to live their culture quietly.

Today many Indigenous people live outside of their home communities. The pull factor is often economic, but the push factors are more often related to Colonial pressures that have devastated native communities. This isn’t to say that reserves and other traditional communities aren’t treasured places to live and visit where traditions are upheld.

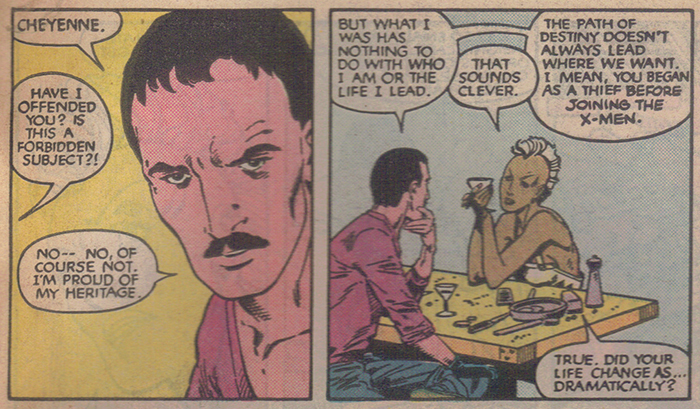

Forge’s Thoroughly Modern Marvel Life

Writer Chris Claremont introduced Forge into his popular X-Men comic book in the 1980s. He was remarkable for a few reasons, including the bucking of a racist trend. Heretofore (and afterwards) native characters tended to have nature and magic based powers – Forge instead possessed the power to invent. He could bend technology to do anything he put his mind to.

Forge was created by Chris Claremont and artist John Romita Jr. The art featured here is by Tony Daniel, courtesy of Marvel Comics.

Also remarkable about Forge is that, while he professes pride in his Indigenous heritage, he also says “it has nothing to do with who I am or the life I lead.” When introduced, he lives in Dallas in a ultramodern loft decked out with hologram technology and often works for the government.

Credit to Claremont again, he introduced a half-dozen or more diverse Indigenous characters into X-Men/Marvel (some better than others). Contrast Forge, for instance, with his fellow Cheyenne, Danielle Moonstar, in New Mutants. Dani straight up tells Professor X that his dress code is bullshit and she’ll include as many Indigenous elements as she wants.

Forge has remained a steady background character – occasionally getting caught up in Cheyenne magical storylines but rarely failing to attack a problem with technology rather than tradition.

That’s his right and it is our expectation, our imagination, that makes it strange or diminishing. A Cheyenne character should be allowed to live how he wants without being doubted as anything less than a full “Indian.”

“Urban mixed-bloods…routinely face demands that they “perform Indianness” in order to have their Aboriginality recognized at all.” Lawrence (2004) Pg 9.

“In the past, authenticity was simply in the eye of the beholder. Indians who looked Indian were authentic. Authenticity only became a problem for Native people in the twentieth century. While it is true that mixed-blood and full-blood rivalries predate this period, the question of who was an Indian and who was not was easier to settle. What made it easy was that most Indians lived on reserves of one sort of another (out of sight of Europeans) and had strong ties to a particular community, and the majority of those people who “looked Indian” and those who did not at least had a culture and a language in common.” King (2005)

But at the same time, ties to the community are one of the cultural markers of Indigeneity across Turtle Island/North America. Forge’s independent modern life is fully his right, but you can’t help but think it is also a little tragic.

“Furthermore, to Indians the very idea of the American hero could only be absurd. While the hero must operate alone, ahead of the rest, for the Indian the community was and is essential to both physical and psychological survival. To be isolated, like all those wandering cowboy heroes, was to have no identity and to perish. To be alone, outside the tribe, was not to be heroic but to have been, in Indian terms, “thrown away.”” Owens (1998) Pg 109.

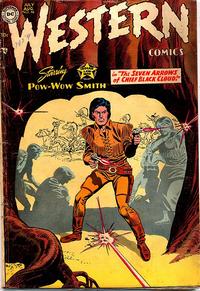

Ohiyesa and the Out-of-Context Indian in DC Comics

In DC Comics Pow-wow Smith (Real name Ohiyesa) is a Sioux character and an “Indian Lawman”, by trade.

He was created by writer Don Cameron and penciler Carmine Infantino. Cameron never specified which branch of the Sioux Nation to which Ohiyesa belonged.

The featured art is by Herb Trimpe, courtesy of DC Comics.

Ohiyesa was introduced in Detective Comics #151 in 1949. His early adventures were set in the “modern” West of the 1950s, where Ohiyesa had been sent by his community to learn “white man’s ways.” The result is broad and silly, but a fascinating turnabout on the “Mighty Whitey” trope. Ohiyesa excels.

Ohiyesa becomes a celebrated detective. Remarkably, and likely because of his acclimation to non-Indigenous society, he experiences little outright racism. The exception is that he is forced to accept the nickname ‘Pow-wow’ rather than his own name

After several years, the Pow-Wow character was moved to Western Comics in 1954 and new creators set his adventures in the Old West. This had no explanation at the time, but was later retconned to be stories of his ancestor of the same name.

(July 1954), artist Carmine Infantino. Courtesy of DC Comics

To be fair, Western Comics were very popular at the time. But the transplanting of Ohiyesa to the Old West speaks to a reluctance to tell Indigenous stories in more modern times, rather than safely in the 19th Century past.

“…when Indians came out in public, whether in the wild west show or the country fair [or in visual pop culture], they exposed divergent views about their role in contemporary Canadian society. Much as the government did not like it, many Whites preferred their Indians in feathers and warpaint. The Performing Indian was a tame Indian, one who had lost the power to frighten anyone. Fairs and exhibitions represented a manipulation of nostalgia. They allowed non-Natives to admire aspects of aboriginal culture, safely located in the past, without confronting the problems of contemporary Native people. “ Francis (1992), Pg 102

To buck this trend and to set Indigenous stories in the 20th (or 21st) century was to buck expectations. Weren’t Indians supposed to be gone? Their presence in the modern day, would be, to borrow a term from author Thomas King, very inconvenient.

The other factor to consider with Forge and Ohiyesa is the cultural genocide practised in the U.S. and Canada, especially through the boarding/industrial school and residential school systems, respectively.

“…the lives of urban mixed-bloods, both in Canada and the United States, are indelibly stamped by processes of diaspora created by government policies designed to sever Native peoples from their communities, such as forced removal from lands in the face of settler encroachment, displacement through residential schooling and adoption, and termination of tribal status.” Lawrence (2004) Pg 6.

Through hardfought activism and cultural care, and struggling still, nations like the Cheyenne and the Sioux are in the process of bringing back their children and revitalizing their cultures.

Ohiyesa’s Chief, who originally sent him to college in 1949 to learn what he could, never intended him to lose his identity. One need not become diminished by mixing in non-native communities.

Do you have another good example of living your culture quietly vs out loud in movies, film, or comic-books? Tell me about it in the comments!

MixedMedia is a blog series Tom is writing based on explorations of his identity as a Métis person, a mixed person, and an avid consumer of pop culture.

Sources

Francis, Daniel. The Imaginary Indian. The Image of the Indian in Canadian Culture. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1992.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Lawrence, Bonita. “Real” Indians and Others: Mixed-Blood Urban Native Peoples and Indigenous Nationhood. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004.

Owens, Louis. Mixedblood Messages: Literature, Film, Family, Place. University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

MixedMedia Chapters

6 thoughts on “MixedMedia Pt 6: Living Your Culture Quietly”