Tom Long, 2024

Dugout canoes continue to fascinate me, as do Indigenous voyages of reconnection. Thus the 1990s journey of the Gli Gli, an Indigenous gommier canoe, in the Caribbean caught my attention.

Gli Gli was the brainchild of two artists, one of whom was Kalinago and the other a white Virgin Islander, and the result of hard work by Kalinago master canoe carver Etiene “Chalo” Charles and their teams. It was a daring project, and the name Gli Gli, or sparrow-hawk in English, is symbolic of the bravery involved in the attempt.

The Kalinago (previously Carib, an exonym) are an Indigenous people of the eastern Caribbean and north-east mainland South America. The post-colonial period has not been kind to their ancient connections. The canoe was the “foundation of precolonial infrastructure” in the Caribbean, according to Isaac Shearn. Dr. Shearn also points out that these canoes were communal projects necessitating large investments of social labour.

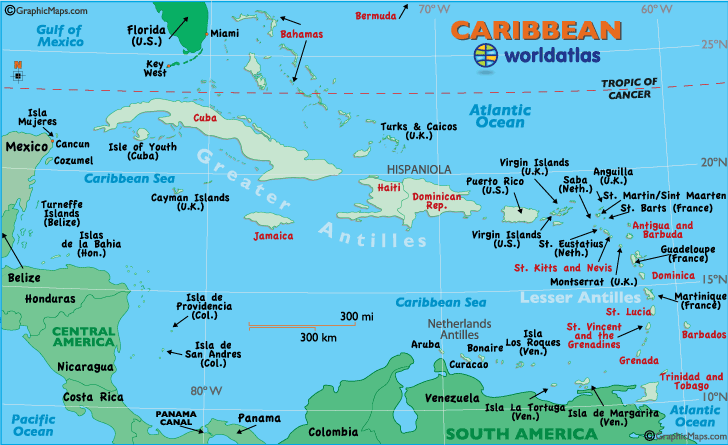

“The ‘Gli Gli’ project constructed a canoe from ancient design using existing technology in Dominica and set sail in 1997 to complete a symbolic and practical journey to reunite the Kalinago with their ancestral and tribal homeland as the canoe and its crew members sail from Kalinago Territory in Dominica down the island chain, through the Orinoco Delta and into the river systems of North West Guyana, where contact was made with Guyanese Kalinago communities.” (A Virtual Dominica)

The voyage of the Gli Gli is another wonderful story of heritage boatbuilding and voyages of reconnection. It is also the perfect project to follow my discussion of the Santa-Maria and other Columbus ships. But after watching the documentary of the voyage, I was also fascinated to dive further into conflict and how it is managed on a replica boat and journey.

Specifications

Not entirely clear, but seems to be 35ft long and “almost 6ft” beam.

Benefits of the Build

Two artists met on a bus. Jacob Frederick, a Kalinago descendant from Dominica , and Aragorn Dick-Read, a white man from the British Virgin Islands. As they themselves describe, they had an instant connection. Quickly they decided that they wished to create and sail a Kalinago canoe together as a project. This was 1994.

Less than a decade earlier, Bill Reid had built Loo Taas and led it on a similar journey of reconnection. In the 1970s, Hokule`a did the same and was still operating. But there isn’t any official record of inspiration. I think it is possible, but I also think that artists and dreamers find easy inspiration in the water and watercraft.

The craft of building these “gommier” canoes was not lost, although it was certainly in danger and decline. The artists hired Etien Charles (‘Chalo’), a Kalinago master canoe builder for the construction. Work began in 1995.

The website “A Virtual Dominica” describes the building process:

- the tree was felled and carved in situ on site) using methods typical of contemporary Kalinago canoe-builders in which the chainsaw is as important as the hand adze (axe).

- Once carved, it took two days for forty people to haul the 35 foot canoe, the largest canoe to have been built in living memory, down to the village of Salybia in the Kalinago Territory.

- The next phase of construction involved “opening” the canoe with rocks, water and fire. This happened in early March, after several weeks in which the canoe sat, weighed down with rocks and doused regularly with water. The heat of the sun and the weight of the rocks inside help the wood to warp outwards and downwards.

- The process climaxed in a dramatic morning at the end of the month in which fires were lit on either side of the canoe allowing it to open considerably.

- The next day the “boardage,” was applied, raising the sides of the canoe and the first ribs screwed in.

- At the end of this stage ‘Gli Gli’ was transformed, with rails measuring approximately four foot in height and a beam of almost six foot

- (all points above from avirtualdominica.com)

The funding for the project was primarily from the C.T. Robinson Trust which included a grant for 10,000 pounds. Aragorn and Jacob seem to have collaborated, as well as raised money through t-shirt sales, etc. They also found a number of sponsors: Quantum Sails in Annapolis, USA; Harris Paints, Dominica; The Paint Factory, Tortola; T and W Machine Shop, Tortola; Richardsons Rigging, Tortola; and Golden Hind Chandlery and Island Marine Supply, Tortola .

“In late November [1995] ‘Gli Gli’ was transported to Marigot, just north of the Kalinago Territory, where final touches were made in preparation for her launch. A ceremony was held on November 30th, with speeches of support from then Kalinago Chief Hillary Frederick and Venezuelan Ambassador Pedro Camacho. Afterwards the canoe was blessed and anointed with coconut water and gommier smoke, before finally meeting the sea. It was a satisfying moment for all of those who had worked on her to see ‘Gli Gli’ catch the wind and sail gracefully out into the Atlantic. In the week of sea trials that followed, she performed extremely well in a variety of weather conditions and allowed the shortlist of crewmembers a taste of the journey ahead. The team was confident of the canoe’s seaworthiness and eager to begin the voyage.” (A Virtual Dominica)

Launching and building with proper protocol is a hallmark of Indigenous craft builds – no less than the Western traditions of boat launch are frequently observed.

Life After Launch

Aragorn Dick-Read and Jacob Fredrick, the project’s leads, planned heavily for the voyage.

“With the help of Dr. John Hemming of the Royal Geographic Society and Survival for Tribal People in London, the team was been able to widen contacts with Amerindian groups, anthropologists, and others in Northwest Guyana and Orinoco regions. On a research trip to Guyana, Dick-Read and Frederick were greatly assisted by Jennifer Wishart of the Walter Roth Museum. Through her direction they were able to make contact with various Kalinago and Arawak communities on the Pomeroon River, all of whom are keen to receive the ‘Gli Gli’ on its arrival.” (A Virtual Dominica)

Film Director Eugene Jarecki joined the voyage to make a documentary, and others joined the crew of the canoe or the support vessel. Most were Kalinago themselves. The initial trip was planned to last two months.

The first few days were not easy – day 3 included their first capsize and day 4 they needed a tow from the support vessel. But each leg of the voyage was about a day, allowing for the primary purpose of visiting Kalinago communities and affirming cultural ties – and also rest for the paddlers. They sold crafts from the beach, further supporting their financial position.

They frequently visited schools and cultural centres. At one, their official log reports “We did our best explaining of the regional importance of Carib culture and started the job of breaking down standard myths about Caribs that have been propagated over the past 500 years. It was an extremely satisfying experience and, although spontaeously put together, served as a good trial for what we would like to accomplish – to educate peoples of the region about Caribs and Carib culture.” (A Virtual Dominica)

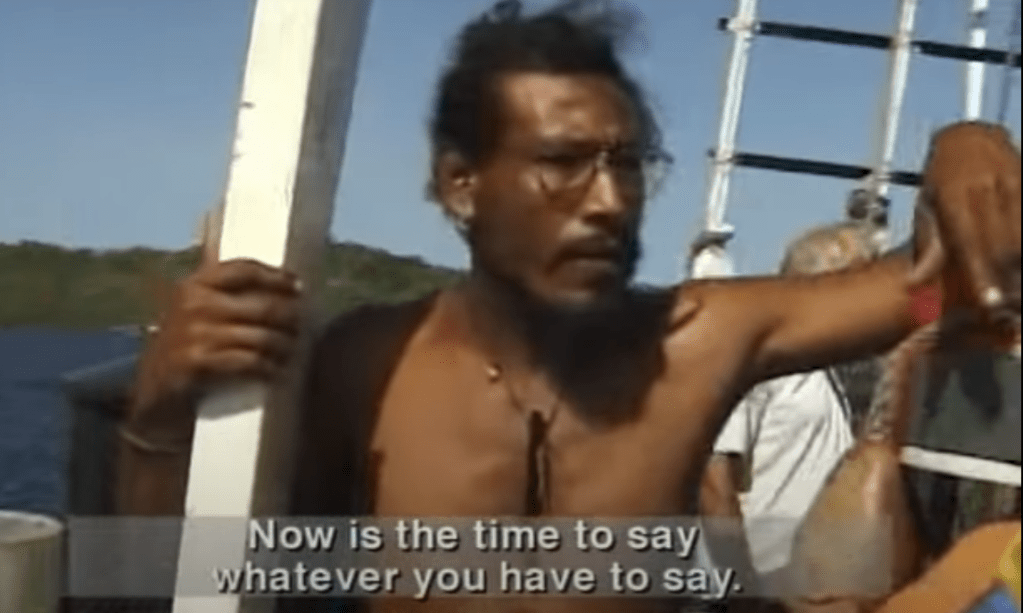

Here some of the textual sources become brief, but the documentary reveals a fascinating challenge. When nearing mainland Guyana, Aragorn confirms that as planned, only a smaller crew will be able to accompany the Gli Gli upriver. Chalo, the boatbuilder, becomes upset that some are being excluded, and threatens to leave the voyage. Aragorn is exasperated, and everyone is tired and irritable. I can understand! After a long journey in close quarters, there is no surprise that conflict arises.

It is only conjecture, but to me this reflects a challenge between Indigenous and non-Indigenous worldviews, as much as it might be a conflict between two persons as well. I suspect that Chalo’s worldview as a Kalinago emphasized sharing resources, inclusion, and consensus. Aragorn, a white man, was responsible for looking after the finances and logistics, embedding him in a Western worldview that prioritised money, transactions, and individual sacrifice.

This is not to say that neither man understood or sympathised with the other’s worldview. Nor that Chalo didn’t understand logistics or that Aragorn didn’t want to be fair. But nonetheless it was a conflict. I’ll touch on this more below.

It isn’t clear how exactly the conflict was resolved from the documentary, other than the crew-member who wanted to come did so. The Gli Gli continued its voyage up the Orinoco on the mainland – often using the an outboard motor (doubtless the cheaper, easier option – something Indigenous voyages tend to not mind, as re-enactment is generally not their primary motivation). They visited with Kalinago communities who had never left the mainland for the islands (As the crew’s ancestors had done) and the journey was altogether a wonderful success in terms of reconnection and culture sharing. The primary aim of the voyage was not necessarily commemoration, but cultural exchange and research – especially in terms of language, traditional medicine, craft and canoe building, and other intangible cultural heritage.

“After return to Dominica the crew continued its mission of reconnection and cultural revival of any remaining First Peoples throughout the Caribbean chain. In 2007 they sailed north and further extended their lei of hope. Now Gli Gli carries school children from Trellis Bay on Beef Island, the far east end of Tortola Island of the British Virgins. The Carib community on Beef Island sells crafts in hopes of founding a school of seafaring for youth of the islands.” (vakataumako)

It seems like the original Gli Gli still survives near Aragorn’s studio, but some of what I have read implies that there is interest in building another boat of even greater size and more voyages.

Further Thoughts

My heart goes out to all members of the crew and this blog certainly doesn’t seem to cast any blame or put anyone “on blast” as the kids once said. Organizing and executing a journey of this magnitude is an incredible feat and only happens when the people involved are incredibly passionate.

And incredible passion can lead to conflict.

Ben Finney has been open about how on the first journey of the Polynesian Hōkūleʻa, the crew encountered arguments and even some physical altercations as they navigated the challenges of their journey. This apparently stemmed from different perspectives of the journey’s goals between Indigenous and non-Indigenous crew members, and the hard work, sacrifices, and hardships of the journey aggravated the conflict. Polynesian Master Navigator Mau Pilag left the canoe after that first voyage because of the conflict, but all crew members reconciled and recommitted themselves to their comradeship.

It is surprising how similar this seems to the difficulties encountered by the Gli Gli. During the documentary, the conflict first seems to erupt between Aragorn and a crewmate over whether there is room for her on the second part of the journey upriver. The conflict escalates, with Jacob encouraging everyone to have their say.

Chulo, the builder of the canoe, insists that everyone who wants to go should go, and threatens to leave the voyage himself if that is not the case.

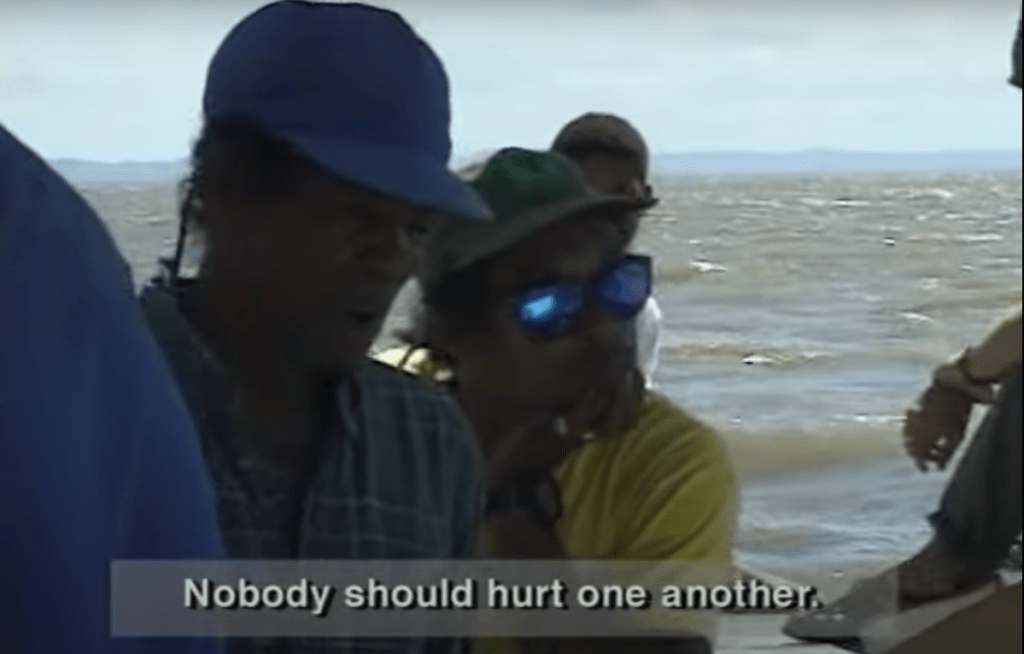

During an exchange, and expressions of personal hurt, Chulo has a powerful moment when he insists on peace.

Again, I do not wish to impugn any of the crew-members, nor lionize any of them either. This is an incredibly stressful moment. We only witness it through the camera lens and cannot assume too much. What we do see is a conflict resolved and, while tempers are high, the journey continues.

But I think one of the lessons to take away from the Gli Gli and other vessels of this kind is how to resolve disputes. A crew on such a journey must and should expect there to be conflict and prepare how to manage it beforehand. My experiences of Indigenous conflict management (in Western Canada) tends to focus on letting people have their say, seeking consensus, and insisting that violence (including verbal violence) should be avoided.

This is not a perfect system either, and I am not trying to say that one method is better than others – merely that there are multiple methods of conflict resolution and some are culturally specific.

The Gli Gli voyage is not always easy to find information on with my limited ability for deep research. I would love to find out more and interview some of the crew members – and especially discover more about the 2007 tenth anniversary journey. This latter voyage interestingly coincides with another voyage in traditional canoes from Guyana to the islands! That project included two canoes, one of 60ft! There is a short video here.

The hour-long documentary of the 1997 journey, directed by Eugene Garecki, is one of the more complete and stunning records of an amazing project and achievement and he and his crew deserve credit – as do Aragorn and Jacob for facilitating the filming – even the parts where the crew is not at their best.

The Kalinago continue to celebrate and re-affirm their culture, even in the face of a larger celebration of their original oppressor Columbus and some preconception that there are no Indigenous peoples left in the Caribbean. The Kalinago were invited to help curate some of the inaurugal exhibitions of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington DC. It opened in 2004. (Shannon, 2014)

Sources

Quest for the Carib Canoe. Directed by Eugene Garecki, No Studio Identified, 2000.

Grimner, John. “Carib Canoe Trial Run Triumph” Domnetjen Magazine. April 2008. https://www.domnitjen.com/articles/caribcanoe/caribcanoetrial.html. Accessed 21-03-2024.

Grimner, John. “Sea Warriors Recreate Carib History” Domnetjen Magazine. May 2008. https://www.domnitjen.com/articles/caribcanoe/caribcanoe.html. Accessed 21-03-2024.

Murphy, Matthew P. “Gli-Gli: A Caribbean Voyaging Canoe” Wooden Boat 201. March/April 2008.

Shannon, Jennifer. “The Professionalization of Indigeneity in the Carib Territory of Dominica” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 38:4 (2014).

Shearn, Isaac. “Canoe societies in the Caribbean: Ethnography, archaeology, and ecology of precolonial canoe manufacturing and voyaging” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology,

Volume 57, 2020,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2019.101140.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278416519300170)

“The GliGli Project” A Virtual Dominica. No Date. https://www.avirtualdominica.com/project/gligli/. Accessed 20-03-2024.

“Aragorn’s Studio on Beef Island in the BVI” BVI Guide, Bareboats BVI. No date. https://www.bareboatsbvi.com/beef-island/aragorns-studio.php. Accessed 20-03-2024.

vakataumako. “Gli Gli Voyage – Traditional Caribbean Canoes” Waka Blog, Vaka Taumako Project (VTP) of Pacific Traditions Society (PTS), May 6, 2016. https://www.vaka.org/post/gli-gli-voyage-traditional-caribbean-canoes Accessed 20-03-2024.

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen or read of around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!