At the time of the build, a moosehide boat hadn’t been seen on the Nahanni in over a hundred years. The trade was not entirely lost, but the Dehcho First Nations were looking for a project that would share those skills and commemorate their past.

Herb Norwegian was the visionary behind the project, but his nation, the Dehcho FIrst Nations invited another nation, the Mountain Dene, with more traditional moosehide experience to participate. Local river guides, and a documentary crew eventually joined the project, which is now captured in the amazing documentary, Nahanni: River of Forgiveness.

This is such a wonderful project to learn about – by reading or through viewing. It is about passing on heritage skills, it is about creating community, and it is about commemoration – all aspects of heritage boatbuilding we have discussed in this blog

The build and voyage was done shortly after Canada’s sesquicentennial, when there was a great deal of patriotic celebration in Canada – a celebration that did not always resonate with the Indigenous people of this land. Heritage boatbuilding, on the other hand, has a way of creating and co-opting its own form of celebration.

“I feel like…following the footsteps of my ancestors.” Herb Norwegian says in the documentary. “[To] make us feel like Dene again…picking up the pieces, crawling out of the ashes of colonialism.”

Specifications

Unclear at this time.

Benefits of the Build

According to the website accompanying the project (riverofforgiveness.ca) “Leon, Robert and Ricky are accomplished boat builders and their niece Corinne and her friend Beatrice are experts in sewing the hides…” These are the representatives of the Mountain Dene mentioned above, who still hold a great deal of boatbuilding knowledge.

There was a larger team of builders on the project, however. It included Elders and young people, making the build both about sharing intergenerationally and internationally between the Dehcho and the Mountain Dene. The non-Indigenous river guides present wanted to help as well, which was welcomed. “Working together is reconciliation too,” Norwegian added during the process.

The crew worked in the spirit of tradition, but with modern tools, even sewing moosehide by the light of a smartphone. The build was about passing on skills, not about “authentic” re-enactment. As with Hōkūleʻa, the goal was the voyage. Geoff Bowie, the documentarian, shows and relates that the impressive thing about the build was the humour and respect involved. Lots of laughter. Some music and singing.

As the Mountain Dene were uncomfortable with the quality of the moosehides provided., the documentary shows a hunt for another moose, harvested with appropriate protocol and respect. This story contains so many examples of Indigenous worldview and practice that I think non-Indigenous Canadians and others will find fascinating.

Much of the work was divided by gender, with men harvesting the timber and women fleshing and sewing the moosehides. Like some other builds I know of, there was some attention to finding spruce trees with natural bends that can be adapted relatively easily into desired shapes without steaming.

The Moosehide boat was a fascinating structure, similar to canoes and European boats, with ribs and a keel. To be perfectly clear, this was not the first moosehide boat built in a hundred years. One was built in 1981 for the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage centre, for example. And others had been built before. But this build and this launch were captured by a documentarian and exposed First Nations people who had not had a chance to experience the build or the voyage before.

It is obvious how impactful the process was. Lawrence Nayally, the host of a popular radio show, shared “Being on the land, it makes me want to feel like I want to be the best Dene I can possibly be.”

Life after Launch

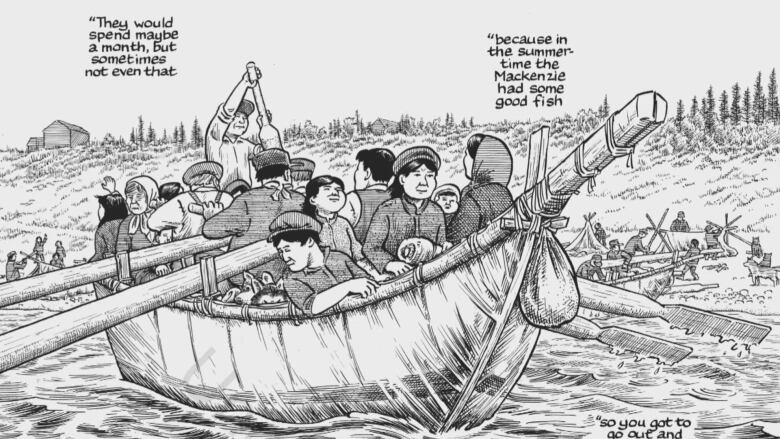

The launch was a very special moment (as most of them are), and done with appropriate protocol. The intention was to row hundreds of kilometres from Bunnybar to Fort Simpson on the Nahanni River. The journey turned out to be worthy of the documentary!

The boat was rowed with three oars and a steering oar, making a crew of four. I’m certain they regretted not being able to build a bigger boat to encompass all of those who worked on the project (they had originally wanted to build a four-skin boat, but ended up using two moose skins for a smaller build). But there was a sharing of rowing duties, and the whole team came along for many of the stops.

The boat was lifted by helicopter over the magnificent Virginia falls, rather than risk portaging it via rollers as would have been done in the 19th century. As with the tools, the emphasis was not on the accuracy of a reconstruction, it was about the community and positive outcomes of reconnecting with river, land, and culture.

Unfortunately by this point of the voyage, several tears were appearing in the hide hull. After examination and consideration, modern floats were used to keep the boat seaworthy. It was towed in this fashion 280km to Nahanni Butte where repair could be considered.

The documentary shows some disagreement at this point. Some of the project team thought that even towing the vessel the remainder of the way was still worthwhile and that the end goal was still to get the boat to Fort Simpson, regardless of method. Others wanted to try a repair so that the rowing could continue – especially since some members of the team still hadn’t had a chance at an oar!

Eventually they decided to attempt a repair, using staples and plywood (quite the “bush fix”!) to patch and reinforce the hide hull. The rest of the 189km was undertaken with the added floats still on, but the vessel was able to be rowed, albeit with frequent baling.

The boat was welcomed to Fort Simpson with what I know of as a feu de joie, or a joyful firing of guns and cheers from the community (this was common in the Canadian fur trade and among the Métis).

The boat was then carried up to land for a photo. It’s not clear to me what has happened to the boat since then. It was in rough shape, and – as I hope has been made clear – it was about the process, not the product. Other similar boats I know of are generally disassembled and the pieces re-used for other products.

The build and the voyage were funded through Indiegogo and the Fort Simpson Historical Society. Geoff Bowie, a documentarian, accompanied them and the result is magnificent. If you are not interested in the documentary (or if you are and you want to expand), the accompanying website tells the story in even greater depth.

Further Thoughts

This was a very special story for me and I think it can and should be for many Canadians and Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island and the world. Through colonisation, the Indian Act, and the genocide of residential schools, Canada has spend more than a century trying to destroy Indigenous beliefs and traditions. Assimilation was always the goal.

This blog about heritage boatbuilding is sometimes about small projects with big impacts. The boat is rarely the point – rather it is about the process and about the people. In this boat’s story you can see so much significance, and so much culture, and so much learning.

There’s also a great deal of symbolism. Leave it to the radio host to provide the perfect ending for the documentary after the arrival at Fort Simpson.

“Lot of holes in this boat.” Lawrence Nayally acknowledges. “Those holes are a representation of the empty promises that Canada has made to First Nations peoples in Canada. And it’s up to our generation to repair it and keep the dream afloat…and we’ve got to do it together… This boat is not about the Dene, its about everybody.”

If you need any more enticement to get a CBC gem subscription to watch River of Forgiveness, you can also watch a National Film Board 10 minute film about a similar build in 1982.

Now go watch “Nahanni: River of Forgiveness”!

Sources

Bowie, Geoff “Celebrating The First Mooseskin Boat On The Nahanni River In A Century” Paddlingmag.com. Oct 2, 2021.

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!