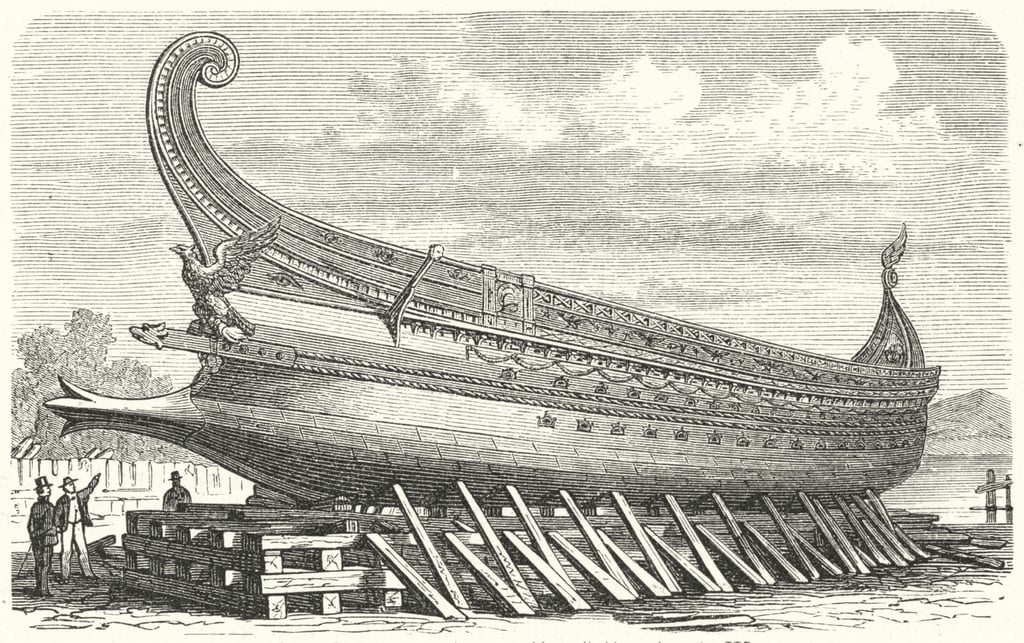

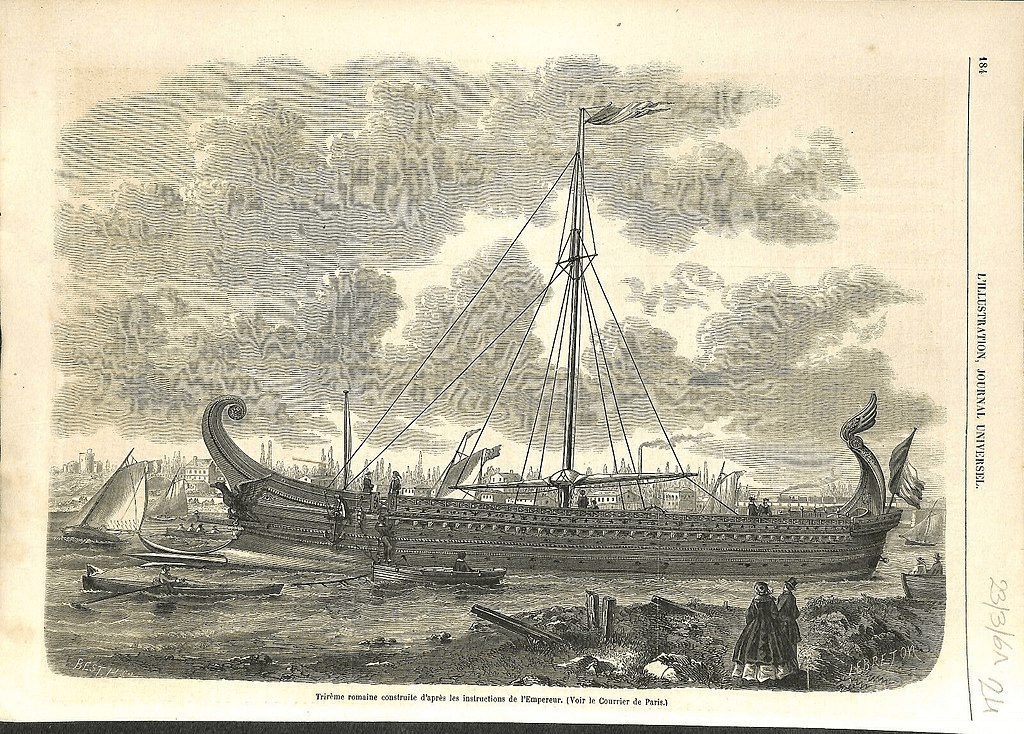

When I first began to delve into the topic of heritage boatbuilding, I wondered what the first modern example of it might be. The earliest I have found is that of Napoleon III and his 1860s efforts to rebuild a classical Hellenic trireme (!).

That’s just a great sentence.

Victorian Europe was fascinated by their Greek and Roman (or “Classical”) forebears, seeing them as the earliest examples of European “civilisation.” It’s not surprising that Napoloeon III would make such an effort, but I would really love to find out more about it. Napoleon III was a patron of maritime building, including an expansion in France’s navy and the building of the Suez Canal, but I believe he was also just an antiquarian. A big nerd.

Modern museums often yearn after nerdy patrons with an interest and deep pockets – although you can become beholden to their whims.

Specifications

According to a photo on wikimedia commons,

Almost 40 mtrs in length and 5.5 mtrs wide. Designed for 130 rowers.

Benefits of the Build

Curiously, no ancient writers have left evidence as to how exactly a trireme worked and how its three (“tri”) rows of oarsmen on either side were arranged (or even whether there was one oar per man). Given that the trireme was a shallow draw boat that could be drawn up on a beach, there is a great mystery as to how this many oarsmen in so squat a ship could be achieved. No doubt that tantalised Napoleon III and his engineers and antiquarians.

Experimental archaeology is the sub-discipline dedicated to recreating ancient practices in order to better understand them. Cooking in clay ovens with ancient ingredients, building and using spear-throwers like atlatls, flint-knapping, and boat-building are just some of the many examples. Discovering how this ancient ship worked by trying to build one is a worthy endeavour, especially in the face of a lack of historical evidence.

A rower on a more recent attempt remarked to the builder, “It must be a wonderful feeling to be afloat on your scholarship.” (Lipke, 1987) I think this evokes the thrilling sense of discovery and accomplishment involved. As a living history interpreter, I wasn’t a serious devotee to experimental archaeology , but it gave me my first taste of heritage trades, crafts, and intangible cultural heritage.

Unfortunately Napoleon’s ship doesn’t seem to have worked out particularly well. The US Naval Institute remarked in 1932 that “The first important attempt to solve [the oarsmen puzzle] was made in 1881 by Admiral Fincati of the Italian Navy in his work Le Triremi.” (Norris, 1932). Poor Napoleon!

Work continued after him and to the recent past. Perhaps one of the kinder things you could say about the Napoleonic effort was that failure can be a great teacher.

Life after Launch

The ship, though much photographed and etched, did not have a bright and shining career. According to one source, it was sunk as target practice. (Lipke, 1987) The above etching implies that it did float, at least for a while (although I note that the etching shows no oars in use).

The efforts to figure out and reconstruct a trireme continued however, and today enthusiasts can see (and even row) a modern reconstruction Olympias, in Athens, Greece

If you know more about this or can recommend some good sources please let me know in the comments.

Sources

Clio’s Armada is a blog series Tom is writing based on his passion for heritage boatbuilding and examples he has seen of it around the world. Read about over twenty examples from the 1860s to the 2010s!

2 thoughts on “Clio’s Armada: Napoleon III and His Trireme”