Tom Long, 2025

I have known I was mixed all my life, but only recently did I take steps to full reclaim my Metis heritage and gain citizenship. I have also been a nerd all my life. My own personal journey led me to reflect on mixed-descent representation in pop culture and how it differs, or is the same as Native or First Nations representation.

This project is not intended to be definitive and encapsulates only a small number of the many films, comic books, and tv shows that have been created. I continue to research and write about mixed-descent Indigenous experiences in my spare time. Please contact me to discuss, correct, or advise.

You’ll find all chapters of this project below.

1: Ethnogenesis or Not

What do Louis Riel, Aragorn, and Katniss Everdeen have in common?

Mixedness can sometime, not always, lead to the creation of an entirely new and distinct identity. When conditions are right, ethnogenesis creates a new nation. Sometimes these new peoples do not survive the pressures of societies with simplistic enforced racial categories. In pop culture, this complex subject is rarely discussed explicitly.

2. An Undiminished Identity

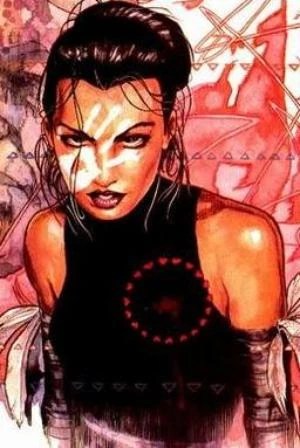

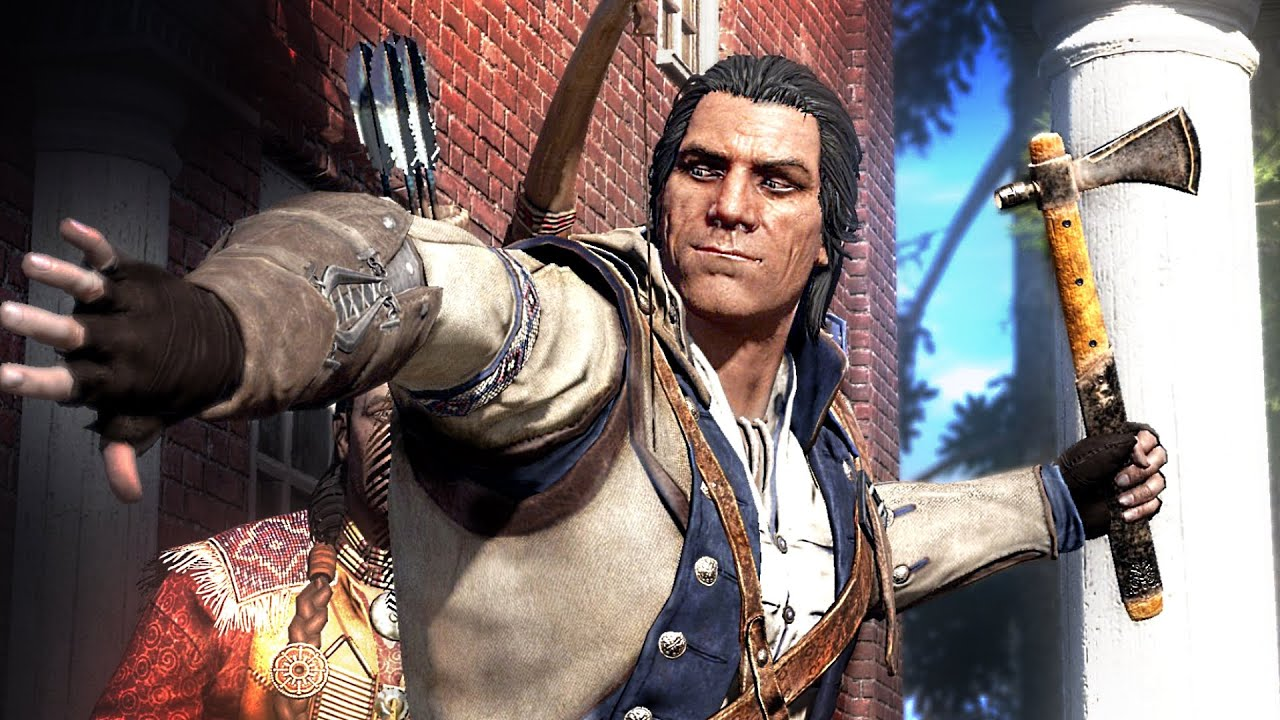

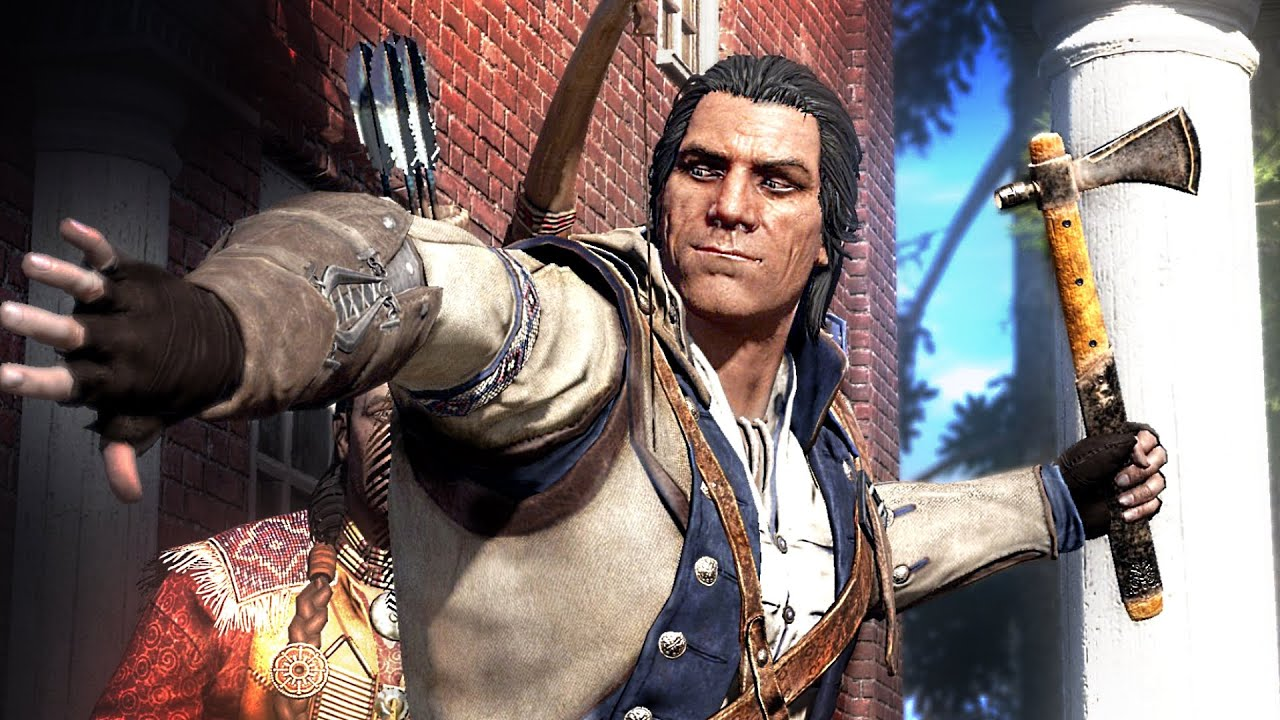

How are Chavez, EloraDannan, and Echo connected to Assassin’s Creed III?

Mixedness can be a plot element for a character while not diminishing identity, a struggle in the real world of the “inconvenient Indian.” Many characters have mixed backgrounds but fully identify with their Nation and in most cases are not seen as less than by their Indigenous peers.

3. Family Divisions

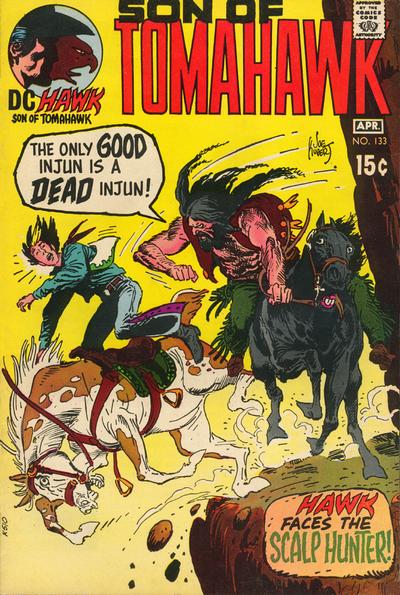

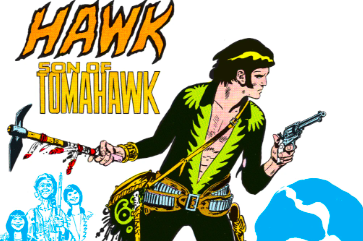

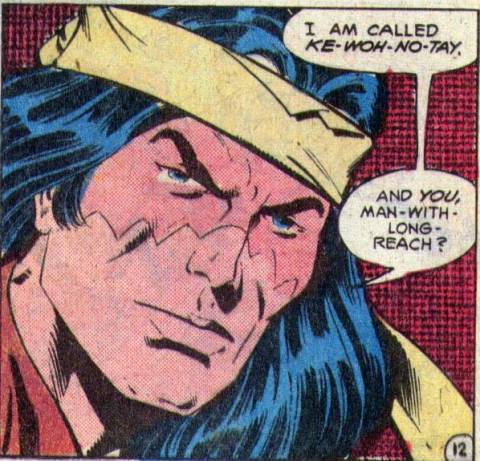

A Deep Dive into Hawk, Son of Tomahawk from DC Comics.

The theme of my first chapter was that sometimes mixedness leads to ethnogenesis (as in the case of the Métis and the Melungeon) and sometimes it doesn’t. The theme of my second chapter was that mixed-descent need not diminish identity.

There is a DC Comic that shows us both themes at once, and in the same family!

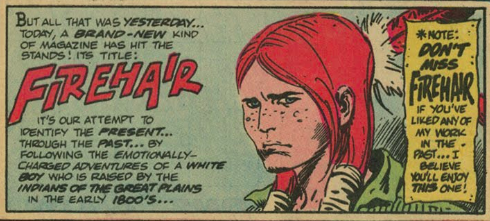

4. Adoption/Appropriation

What do Speedy, John Dunbar, Jake Sully, and Daniel Day Lewis tell us about adoption and appropriation?

Adoption is a legitimate way for all families and nations to accept new members. Many Indigenous nations have long traditions of this practice, allowing them to adopt and absorb new persons and therefore create kinship ties to secure alliances and end hostilities, among other benefits. Adoption, however, creates problems for modern restrictive views on nationhood, and also creates dangerous opportunities for appropriation and pretendianism. In pop culture it often leads to the “white saviour” trope.

5. A Volatile Mixture

How do Namor, John Wayne, Clara Bow, and K’Ehleyr fit together?

Mixedness is often used in pop culture to create and heighten drama by having the volatility of a character’s mixedness lead to an internal and external struggles. This is often connected to the “tragic hybrid” idea of being torn between two worlds. TVTropes calls one aspect of it “Half-Breed Angst.” This sort of angst seems to be much more prevalent in fiction than in reality, based in mainstream society’s ideas about biology, race, and racial essentialism. But you can see the screenwriter’s desire to make an internal conflict external.

6. Living Your Culture Quietly

What do Forge and Ohiyesa have in common?

Mixedness is not always about blood quantum. The perception of how prominently the person is living in their culture can lead to impressions of being diminished or diluted. But that perception also pressures Indigenous people to live a “plastic shaman” or “feathers and buckskin” version of their culture. There are also factors, including policing and legitimacy in academic or professional circles, that might pressure Indigenous people to live their culture quietly.

7. A Convenient Indian Ancestor

Rambo, Lt. Aldo Raine, Frank Hopkins, etc, etc, etc.

Mixedness in pop culture can often be simplistic, and intended to serve a single story or character point (often a stereotypical one). This isn’t just found in movies and comic books though, you can also find the many-times-removed descendant of a Cherokee Princess in academia, politics, and casual conversation.

There isn’t anything wrong with being proud of such a link, but problems come in when persons with a “convenient Indian ancestor” take grant money, positions, or prestige from Indigenous people with less privilege. Or when the claim is made with no awareness of the complexities around it.

A Note on Nomenclature

I have generally used mixed, mixed-descent or mixedblood throughout to refer to persons with both Indigenous North American and other ancestors. Halfbreed is a term I’m not fond of, but some mixedbloods have been reclaiming it. Métis is a term for the Métis Nation, who are not defined by their mixedness. I find biracial is used more often for African-American mixed descent so have avoided it, but that’s not a judgement if you want to use it.

First Nations and Indians have been used fairly frequently, although I tend towards the Canadian “First Nations.” I occasionally use “Indian” when dealing with what Daniel Francis calls “the Imagined Indian” of Western fancy. Native and Native American are also appropriate but I find it a bit more confusing with Métis in the mix – who have historically been called Natives as well.

Indigenous as a term encompasses First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and others. But hard and fast dividing lines between Indigenous and non- are colonial in nature – even if they are sometimes legally and morally necessary. There are some mixedbloods who are Indigenous and some who aren’t. Sometimes I think its clear and sometimes its not for me to judge (neither is it for colonial governments). Rarely is it simple.

MORE TO EXPLORE

Good Reading

Aleiss, Angela “Indian Adventures and Interracial Romances”. Making the White Man’s Indian: Native Americans and Hollywood Movies. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2005.

Donahue, James J. Indigenous Comics and Graphic Novels. University Press of Mississipi, 2024.

Francis, Daniel. The Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian Culture. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 1992.

King, Thomas. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

N.b. Thomas King recently admitted that he could not prove the Cherokee ancestry he has claimed all his life and ceased to identify as an Indigenous person

Lawrence, Bonita. “Real” Indians and Others: Mixed-Blood Urban Native Peoples and Indigenous Nationhood. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004.

Owens, Louis. Mixedblood Messages: Literature, Film, Family, Place. University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

Good watching

(These are great sources in general for Native and mixed representation in media, but don’t touch on mixedbloods in specific.)

Princess Weekes “Tall, Dark, and Racially Ambiguous” August 29, 2024.

PBS Origins “What Hollywood Gets Wrong About Native America” May 21, 2024.

Diamond, Neil. Reel Injun. Produced by Neil Diamond, et al., Lorber Films, 2010

STORYTELLING

At heart I am a storyteller, and have a whole selection of presentations I can give in person (Lower Mainland, British Columbia) or virtually – including on MixedMedia.

MIXEDMEDIA: Mixed-Descent Indigenous People in Pop Culture

Length: 1 hour (45 minutes plus discussion time).

Recommended audience: 3-30 persons

Delivered via: Zoom; Google Meets, in person (Lower Mainland BC).

The bulk of literature on Native representation in pop culture has not included “halfbreeds,” mixedbloods, Métis, or other examples of mixedness. The stories of Chavez in Young Guns, Katniss Everdeen in The Hunter Games, Connor Kenway in Assassin’s Creed III, and Hawk, Son of Tomahawk from DC Comics are only a few of the examples we’ll look at. Join me to discover what pop culture’s mixedbloods can tell us about how mixedness is perceived through movies, comics, and tv series.

To enquire about this presentation, drop me a line!